Recently, I wrote my very first technology strategy. Overall I’d say the process went pretty well. Of course writing the strategy is intimidating to begin with, but once I started I quickly realised that the much more intimidating thing is actually working to implement the strategy after it’s written.

I felt and still at times feel like fleeing to the woods to live as a wolf as a result of this realisation but I’m pretty sure my life insurance has exclusions for fleeing to the woods in order to live as a wolf. It’s not the family oriented response you think it could be, despite wolves being good family members that live in packs.

Anyway, these (broadly) are the steps I took to create my strategy, this article intentds to describe systemically and procedurally, how you might create a technology strategy (or any other kind of strategy for that matter).

- Identify the stakeholders to the strategy

- Interview the stakeholders to understand the scope/expectations

- Draft terms of reference based on the outcome of 2.

- Present the Terms of Reference to the stakeholders and seek endorsement

- Based on the agreed terms of reference go forth and gather data

- Use Confluence to build out a template starting from the Terms of Reference

- Link to relevant frameworks/models through Confluence for reuse via other strategies

Note

This is all going to be a bit cerebral. The strategy is the cognition; that informational content that provides a bounded context, assumptions and input data about that content.

This page then, is meta-cognition. It’s about the process and procedures with which you might structure your thinking, synthesise large amounts of data, discard data that is immaterial to your cognition and crystalise and reduce the remainder down to guidance that can be given to your audience.

The intent of this page is not to be procedural, if you’re looking for a clickbait article of 9 top tricks to produce a killer strategy (Consultants HATE them!) then you’re going to be disappointed. This is all about developing your own method within a cognition framework that encourages a focus on context, assumptions and implications where the analysis of that context is deep enough and clear-eyed enough that

Corporate Context

Eben Hewitt, in his book Technology Strategy Patterns, states:

In any business, there are patterns of work, at work within the business. These patterns are crucial to your success and their effectiveness may vary. Your job as a strategist is to understand the patterns and processes in your area of concern and use them to achieve your goals. Your job as a strategist trying to influence and create change will be vastly more difficult if you oppose these patterns and processes.

In other words, don’t fight the plumbing. Understanding and describing the corporate context you operate within significantly increases your chances of success. Your goal is to use the existing patterns to change the patterns. Don’t fight the plumbing, co-opt it.

Hewitt goes on to say:

The way to be successful in a company is to do something that matters to someone who matters. Projects that don’t matter to the people who matter are misaligned. Eventually, someone will ask about the line item on the budget spreadsheet. If nobody in the room knows what it is or why we’re doing it, odds are that it’ll be sidelined or cancelled. Aligning yourself with that project is a waste of your time and a waste of the company’s time. If you somehow manage to complete your misaligned project under the radar, you will soon find that your project was thriving only because it was under the radar. The impact to the company is once again a waste of time and resources as a result of the misspend, and a delay in the chance to complete the strategic stuff.

Your first job then is to identify the people who matter. This is nothing more or less than old fashioned stakeholder management. Stakeholder management is crucial to your success in developing a strategy for the reasons described above. If you are not aligned with them, you will struggle to produce value.

Note

As a general rule, I tend to consider strategy work in timeboxes. Of the timebox I allocate, I will typically spend 15%-20% of the available time working with stakeholders.

At the start this might look like meeting to discover their needs and expectations, during the process it might look like giving them updates on progress or drawing out their feedback. At the end of the process it might look like individually briefing your stakeholders in a ‘meeting before the meeting’ style (more on that later).

The amount of influencing and managing you will have to do will depend on how closely aligned the things you are proposing are with the way your stakeholders think and feel. If you’re proposing a radical departure from the status quo, expect to spend more time talking to folks and ensuring they are on board.

Warning

Not every leader recognises the centrality of strategy. These folks may just prefer to wheel and deal, valuing sensing and response over planning, implementing and measuring. They may be passive in your process, ignoring you as they hope you are a flash in the pan that eventually burns out. They may actively undermine you as your strategy encroaches on their percieved fiefdom, or they may seek to discredit you or your strategy. They may view you as an astronaut, so high up you can’t see the daily operation of the business.

Be careful with these people. Include them in your stakeholder analysis. If they oppose you, it might be because they are right! They might know something you don’t, so lean in and engage them. If you can convince them, they will be a strong ally, and if you can’t, they will make your life difficult. Your stakeholder analysis will show you the approach you need to take with them.

Determining Stakeholders

In order to achieve something meaningful, you must first understand the org chart and start at the top. Start with the CEO and the other members of your executive team. If your strategy does not matter to these people, it will fail. (Note that I’m writing this in the context of a smaller business. Fewer than 1000 folks but more than 50. An organisation where you as a strategy-maker would reasonably expect to bump into a random executive team member in the kitchen at lunch time once or twice a week. If your organisation is bigger, replace C-Suite member with a suitable director level role e.g. VP, Head of, GM etc)

There are three groups of people with whom you must be aligned:

- The folks who will pay for it and stand on a stage and tell others that it’s important (i.e. your leaders and executive team)

- The people who will execute it, and need to understand it well enough to execute it properly (the teams and individual contributors doing the work)

- The people who will ignore or undermine it if their views, aspirations or concerns aren’t represented (your peers)

You must have a 360-degree view of the organisation. That view will help you understand how your organisation works, how things get funded and where the bottlenecks might be.

Determining Drivers

Identify which leaders in the business matter in terms of your strategy. These people will reside across the organisation. They won’t be restricted solely to your business unit. It’s not enough to work in the context of a single function of the business. You will have to learn to communicate and collaborate cross-functionally.

Consider the different parts of the value chain your business implements (if you’re not familliar with value chain analysis - What is a value chain analysis? is a great resource) - Inbound Logistics, Operations, Outbound Logistics, Marketing and Sales and After-Sales Service (consider the supporting functions as well). Your strategy will not be the right strategy, and will not be supported or effective if you do not consult key leaders in these organisations.

It’s not practical to consult with everyone, and you should avoid rule by comittee. If you read anything in your strategy that looks like it could it might have come from a cat poster you saw at the dentist, it’s a sign that you’ve gone too far down that track.

Of the folks, you’re thinking about talking to, who stands out as powerful? Good leaders will try and make it look like they love all their reports equally, in reality, they do not. Reaching out to these people for their feedback and input has the additional benefit of making them aware of your strategy.

A fictional example, provided by Eben Hewitt in his book, Technology Strategy Patterns:

The mergers and acquisitions team might be two people in a room with no budget to buy anything and little of consequence to do. If the view is that building things ourselves is too risky and error prone, the M&A team might be very large and well funded (i.e. powerful) and busy buying another company every week. In such a case it’s important to consult with them as their input matters more. Your strategy should reflect that.

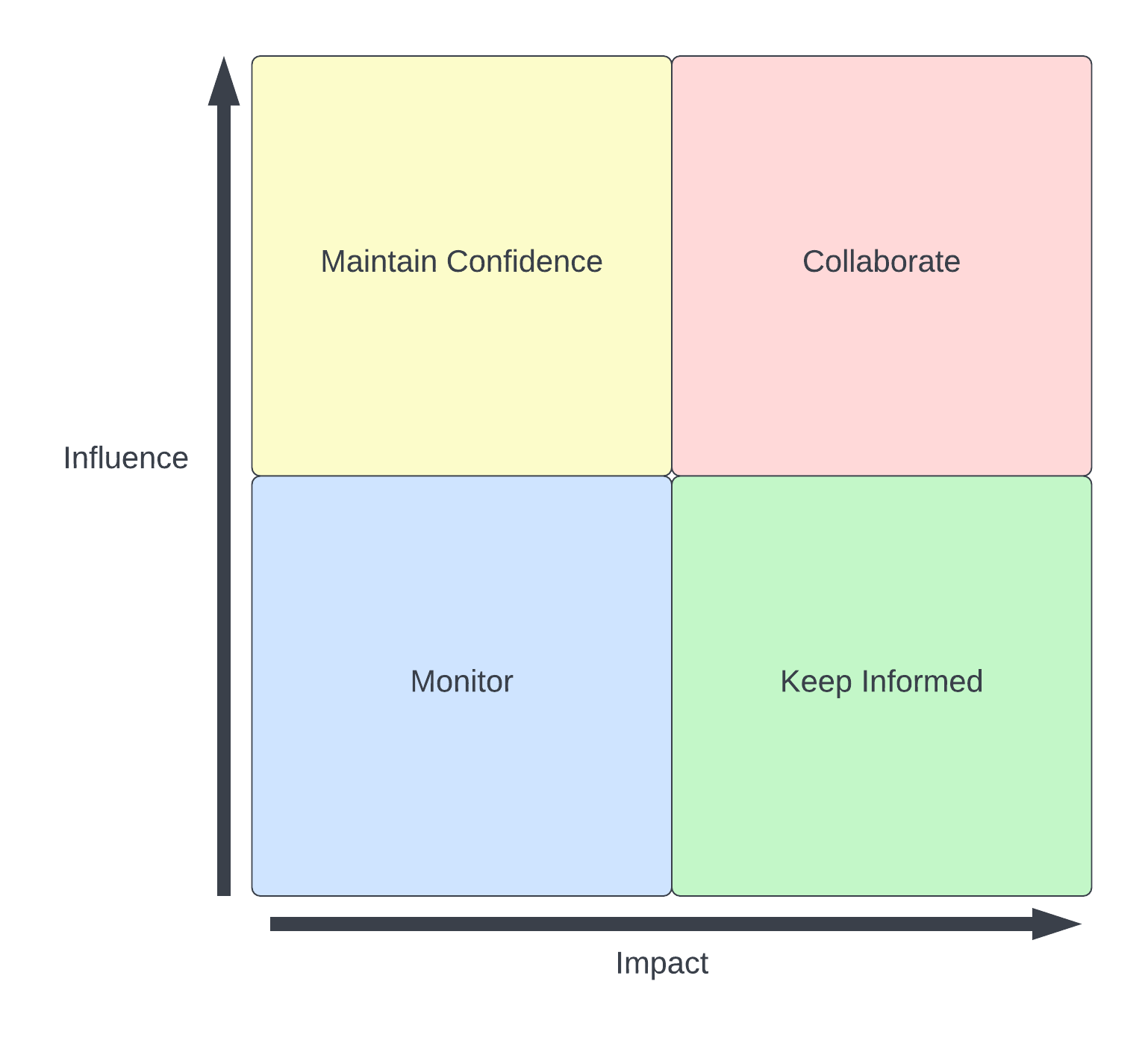

Stakeholder Matrix

Different stakeholders will have different roles in the context of the development of your strategy.

Create a list of all your stakeholders with two columns:

Influence

Influence refers to how important this person’s support is. What is their level of control over your destiny? Do they control funding or determine timelines or other constraints? How able are they to materially change the detail or direction of your strategy?

Impact

Impact refers to the degree to which, when realised, your strategy will impact them. If your strategy is to consolidate multiple products into a single product, your strategy will have a large impact on the sales, product and marketing teams. If you’re proposing we outsource software development to a third party, your impact on the members of the technology department will be extreme.

Score each stakeholder you know of on a scale of one to five for each column and generate a 2x2 matrix.

Quadrants

I really love the wording Hewitt uses in Technology Strategy Patterns to describe the different ways in which you should interact with folks depending on the quadrant they are situated within:

Monitor

Ask them on a regular basis how their work is going, and what’s coming up for them. Note what might inform your work. Check in occasionally about their work and yours. If these folks have a broader understanding of what you are doing and they understand why it can create support that may come in handy later.

Maintain Confidence

Invite them to steering meetings for your strategy. Send them updates on your progress. Be sure they understand the milestones and know how you are tracking against them. Ensure they understand and approve of your metrics for success. Ask them for insights that might modify your strategy. Follow up on their continued buy-in on your roadmap. Discuss your progress regularly and in detail.

Keep Informed

Invite them to larger forums for updates, such as town halls. Talk with them about work they may need to prepare, such as communications, training, departmental updates and so on. Go to their meetings to present specifically to their teams.

Collaborate

Actively work with these people on a regular basis in full partnership to co-create the ideas and execution plans within your strategy.

Setting Terms

Identifying stakeholders makes your life as a strategist easier. You have a list of people who care to different degrees, and you have an idea about what drives them, and the relationships they value.

The next job is to listen deeply to them. I call this process setting terms. The metaphor I use here is an investment one. Term sheets are an investment tool whose intent is to clearly outline the details of a deal. They describe the parties, they describe the agreement and they describe the investment.

You as a strategist are investing a portion of your life into the creation of this strategy. Creating strategy is a time-intensive thing, that time is very valuable in terms of salary, but even more valuable in terms of the opportunity cost. If you might spend six weeks creating a strategy - what else could you do with that time?

Providing a term sheet upfront, before you begin work in earnest will give you the confidence to know that you’re:

- Asking and answering the right questions

- Supporting the right activities

- Creating space for the right conversations

A term sheet is a powerful statement of support that will help you in the creation of your strategy. It’s a document that clearly articulates what you’re doing and why, and who your backers are. This can really help get traction with folks you need support from - it’s an instant way of helping them understand what you’re doing and create shared goals.

Collecting data via Stakeholder Interviews

Your next step is to collect the data you need to understand your terms of engagement.

With your stakeholder analysis, you have the information to know who your key stakeholders are. Your next step is to meet with those folks and listen to them.

The size and rough impact of your strategy will dictate how wide you need to go, as a starter, I’d book half-hour sessions with everyone who you have added to the ‘collaborate’ bucket. Time permitting, you should also interview all of the folks you’ve added to the ‘maintain confidence’ bucket. I don’t recommend interviewing either the ‘monitor’ or ‘keep informed’ buckets - there will be too many people in this group to interview and the resulting term sheet will be diluted by too many voices - strategy by committee is ineffective, so too are term sheets by committee.

What do I ask them?

Your goal in these interviews are two:

Create confidence in the interviewee that you are listening, and that you hear and understand their point of view

Find out the general and specific areas that your stakeholders want you to address in your work, as well as an idea of outcomes, how they might want your strategy to be implemented as well as their preferred way of interacting with and understanding your strategy

Here are the questions I asked my stakeholders:

What do you need from the digital strategy?

What are the key points you want the strategy to address?

What kinds of concrete outcomes or activities should we be able to derive directly from strategy?

How do you want to feel after having read, been presented or otherwise consumed it?

Warning

It’s possible to produce a good strategy without going through this process, but your chances of

- Failing to build and maintain confidence with stakeholders

- Producing a strategy that cannot be acted on

- Producing a strategy that does not address the concerns of the business

increase dramatically if you do not know well, and are not constantly talking to your stakeholders.

With the raw data from these interviews collected, you can begin to boil it down into terms. You may have to go back to clarify several times. You may have ideas from stakeholders that clash or are incompatible. That’s okay! Add them to the terms regardless. One of the benefits of this document is that it will make clear where your stakeholders do not agree, the terms will give you an option to work through and solve that disagreement in a neutral and unbiased manner. At the same time, going through that process with your stakeholders will build trust - trust is a critical resource for you to manage.

Closing on the terms

With a draft term sheet in hand, your next step is to get agreement. Your end goal is a meeting in which all of your stakeholders express that there is nothing particularly controversial or bold in the terms and that it all makes complete sense - it’s the natural thing to do!

That’s not to say your terms aren’t radical! The strategy should be strategic! The point is that by the time you get the final meeting to ratify the terms, all of your stakeholders have seen them a few times. They see themselves in the terms as a result of your interviews with them. They see the needs they express are being met and even some needs that they didn’t express (helpfully their colleagues expressed those ones!).

There shouldn’t be much discussion at your final meeting. You should open by reviewing the terms and the process that got you all there, and then ask for ratification. The meeting should feel like a fait accompli.

How is this possible? You should be having the meeting before you have the meeting.

Book a second round of meetings with the stakeholders you initially spoke with, and brief them on the term sheet you’ve developed. Use this time to pay attention to their individual needs and answer any questions they might have. This is a good opportunity to road test your ideas and ensure that you have drawn the right conclusions, and synthesised the many different angles of feedback from your stakeholders appropriately. For more detail on pre-meetings, see When it’s worth having the meeting before the meeting fair warning, it’s HBR and very American.

Building your strategy

With a group of folks behind you and an agreed outcome, the next step is the fun part! Now you get to create your strategy and show your vision, knowing that the whole business is behind you and wants you to succeed!

I believe that good strategy has two key jobs:

- Share Context

- Make Assertions

The goal of a strategy is to clearly articulate a situation and plot a course through it. The nature of any strategy is that it is actionable. It guides us. In the same vein, every statement you make should be falsifiable. The thing that differentiates strategy from vision is action.

Your strategy should primarily consist of assertions. With the full body of context behind you, you can draw a clear line between the context you observe and your assertions about how to respond to that context.

Info

If your argument cannot be proven correct or incorrect, it cannot be measured and so cannot guide behaviour - strategies are about guiding behaviour.

In other words, the contents of your strategy and the points you address are defined by your term sheet. The way that you respond to the term sheet should be informed by the context. That response is your strategy.

The specifics of how you write and communicate your strategy are entirely up to you, and I offer the following advice:

- Keep talking to stakeholders, be visible in what you are doing and seek feedback throughout the process

- Your strategy should be practical. It should be easy for folks to read it and answer their own questions about what they need to do. The reader’s next steps should be clear to them.

- You can make those next steps clear, by making clear assertions that are informed by context. These may take the form of “Given X, we should Y, therefore we need to Z.

- With your writing, you should be optimising for the reader. Optimise for them, their time, the way they break down and understand information. Optimising for the person reading your strategy is much more difficult then optimising for the writer!

Tip

When using lists, ensure they are MECE (pronounced “mee-see”) MECE is an acronym for Mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive. MECE dictates the content, not the format of your list. Ensure that you are constructing your content such that it relates to a specific audience.

Here are some examples. The following two lists are MECE:

- True, False

- Summer, Autumn, Winter, Spring

The following two lists are not MECE:

- Spruce, Cedar, Oak

- Light, Dark, Bread

Lists that are not MECE invite doubt into the mind of your reader: “Are these all the options? Is there a missing concept here? Are the things being listed comparable?”

Consider another good example from Technology Strategy Patterns, the following formula:

Revenue - Cost = Profit. Free Cash Flow

Hewitt explains that

this formula is not MECE because free cash flow is at a different level then the others. It is true that free cash flow is an important financial measurement, but that is unrelated to this equation. Even though they all appear to be related to “stuff about money in a company” the concept is not sufficiently directed to an audience, for a goal.

Documenting your strategy

Regardless of the content of your strategy, it’s going to involve words. Knowledge. Ideas. These things will evolve and grow over time. You will need to store these things somewhere visible and accessible, searchable and editable. You will need to engage in conversation pertaining to specific things you have said. You will need to demonstrate that you are listening and adapting to feedback.

Your company’s knowledge management solution is the place for this. Notion, Confluence, find a space or create one, and put your strategy there. Your strategy being words, will be wordy, and few people may want to read all of it. That’s okay. You’re creating a reference.

Once you have strategy published and it’s some degree of complete, you’ll be able to create products from that strategy to suit the audience and the message.

Consider the words in your knowledge managent solution like a big bowl of dough. That’s a lot of calories. It’s big, carb-heavy. Could take some time to get through in it’s current form. Sweet Jesus that’s a lot of calories. With this documentation you are creating an encyclopaedia for folks to take what they need. We don’t expect anyone (except my seven year old becuase he loves it) to take the encyclopaedia from the shelf and read it from start to finish in one sitting.

Warning

Many people will tell you “Writing is a waste of time! Nobody will read it!” I disagree. Writing is the way you scale your career. Writing is the way you scale your business. Writing is how you create impact and share ideas. It is timeless and durable.

If you get your term sheet right, people will read it. More then that, they will want to.

Presenting your strategy

You cannot ask sixty people to sit on a teams call and listen to you read out loud, no matter how velvety smooth your voice is. When it comes time to present your ideas, take a slice. Cut off a piece of dough and shape it and bake it however you need.

In this case, I would recommend a slide deck or shorter written summaries - think flash cards, not short stories. You can create as many slices as you need, that target and speak to as many audiences as you need, to any level of time. Having the full strategy written and held elsewhere makes it infinitely flexible when it comes time to present, and that is a very powerful capability to have in your back pocket.

There are two facets and five cuts you might like to consider as default options. Pick one facet and one cut, and you have a purpose built communication tool specific to your audience and their context.

Facets:

- Technical

- Non-Technical

Audience Cuts:

- Board

- Executive Team

- Department Managers

- Entire Department

- Entire Business

To produce individual decks addressing all of the combinations of facet and audience is made much easier by having the complete documentation live elsewhere. It becomes a case of pulling the relevant data and message into each deck - and there is no need to do them all at the start, it takes so little time to recast that you can do it as needed, rather than upfront.

Implementing your strategy

This section is left intentionally blank, as an exercise for the reader.

Summary

Creating strategy is hard work. Implementing it is harder!

Your strategy will live within the corporate context of your organisation. It will be dictated by your organisational design and the individuals who fit within that design.

You will need to identify the folks who matter to your strategy, and win them over. Further, you’ll need to manage stakeholders with varying goals and varying centrality to your strategy, and you will need to work with them and their processes, not against them.

Consider that in writing your strategy you are creating a desk reference on where we are going. Expect to take that volume and streamline it for the time, place and audience - and optimise for them, not for you.

References and further reading

[1] Technology Strategy Patterns - Eben Hewitt

[2] What is a value chain analysis? - Tim Stobierski, Harvard Business School

[3] When it’s worth having the meeting before the meeting - Andy Molinksy, Harvard Business Review

[4] MECE - Wikipedia

on Unsplash](https://4lex.nz/img/post-bg-strategy-development.jpeg)